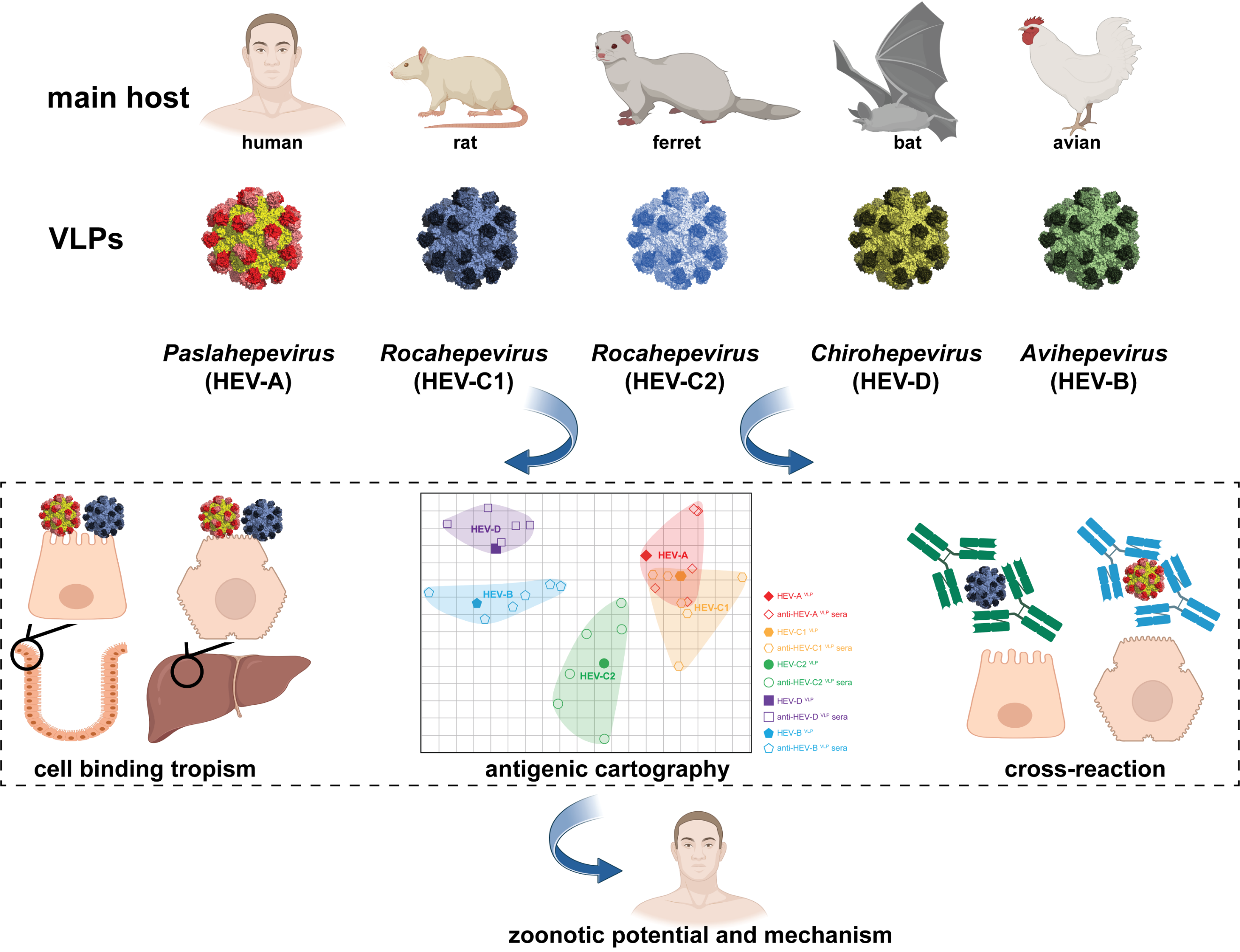

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is the most common cause of viral hepatitis worldwide, with estimated 20 million infections and around 60,000 fatalities annually. Distinct from all the other human hepatitis viruses, HEV is the only one that is zoonotic. HEV belongs to the Hepeviridae family divided into two subfamilies: Orthohepevirinae and Parahepevirinae. Orthohepevirinae includes four genera that are phylogenetically distinct and have different host ranges. They are classified as Paslahepevirus (referred to as HEV-A; including eight genotypes HEV-1 to HEV-8; isolates from humans, swine, deer, mongoose, rabbit, and camel), Avihepevirus (referred to as HEV-B; isolates from avian), Rocahepevirus (referred to as HEV-C; isolates from rat, greater bandicoot, Asian musk shrew, ferret and mink), and Chirohepevirus (referred to as HEV-D; isolates from bat).

Classically, human diseases are thought to be exclusively caused by Paslahepevirus. However, increasing cases of hepatitis E have been reported to be associated with the infection of rat HEV in multiple regions across the globe since 2018, and recently, two children with acute hepatitis of unknown origin were found to have rat hepatitis E virus infection in Spain. This indicates that rat HEV, which is classified as HEV-C1 clade of Rocahepevirus, can cross species barrier to cause zoonotic infection in humans. The zoonotic potential of these genetically distinct HEV species has raised great public health concerns. Therefore, it is of great importance to dissect the mechanisms of zoonotic transmission potential of different HEV species.

A recent study led by Dr. Wenshi Wang from Xuzhou Medical University, China, in collaboration with Dr. Siddharth Sridhar from the University of Hong Kong, dived into the mechanistic insight of HEV zoonosis.

Viral entry is the first determinant of host tropism and the ability of cross-species transmission. This step is initiated by specific binding of virions to the receptor(s) on the cell membrane. There are two forms of HEV particles in the infected host. In general, the naked, nonenveloped virions (nHEV) are shed into feces to mediate interhost transmission, whereas quasienveloped virions (eHEV) circulate in blood to spread the virus within the host. Therefore, the entry of nHEV through direct interactions between the viral capsid and cellular receptor(s) is one of the key determinants of host tropism and zoonotic transmission.

The researchers took the advantage that the HEV capsid protein ORF2 can assemble into virus-like particles (VLPs) in vitro. These VLPs are believed to mimic live viruses in binding and penetrating host cells, constituting a good model for studying viral entry. Then they generated VLPs for all HEV species and comparatively assessed their host tropism in multiple cell lines and human liver and intestinal tissue slides. Intriguingly, rat HEV (HEV-C1) VLPs bind to human liver and intestinal cells/tissues with high efficiency and specificity. Moreover, HEV-C1VLPs penetrate the cell membrane and enter target cells post binding. This observation was further confirmed by employing infectious rat HEV particles. In contrast, ferret HEVVLPs showed marginal cell binding and entry ability, bat HEVVLPs and avian HEVVLPs exhibited no cell binding and entry.

Antigenic cartography indicated that rat HEV exhibited partial cross-reaction with HEV-A. More intriguingly, HEV-AVLP immunized rat sera, HEV-A infected patient sera, and human HEV vaccine Hecolin® immunized individual sera partially cross-inhibited the binding of HEV-C1VLP to human target cells. These findings revealed mechanistic insights into the distinct zoonotic potential of different HEV species and elucidated their cross-species antigenic relationships and serological responses.

In summary, the interactions between the viral capsid and cellular receptor(s) regulate the distinct zoonotic potentials of different HEV species. The systematic characterization of antigenic cartography and serological cross-reactivity of different HEV species provide valuable insights for the development of species-specific diagnosis and protective vaccines against zoonotic HEV infection.

Read the full article Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024 Nov 5;121(45):e2416255121. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2416255121